Why we wrote this guide

The purpose of this guide is to give the reader a fundamental understanding of what a music publisher does, as well as a sense of how their business models are changing and adapting to the digital age. This guide includes detailed descriptions of the inner workings of the typical music publisher, an outline of the different types of publishing deals a songwriter may encounter, and some historical background and context as to how the music publishing industry came to look the way it does today.

Who This Guide Is For

- Songwriters thinking about signing a music publishing deal

- Those interested in a career in music publishing

- Business owners and employees of music publishing companies, or of businesses who interact with them

Contents

Overview

Background

The Publishing Deal

What a Publisher Does

Different Kinds of Publishers

A Short List of Publishers

Advocacy Groups

Overview

A music publisher is fundamentally responsible for licensing and administering the composition copyrights of songwriters. An important distinction to note is the difference between a composition copyright and a sound recording copyright. A composition copyright pertains to the collection of notes, melodies, phrases, rhythms, lyrics, and/or harmonies that make up the essence of the work. A sound recording copyright pertains to a particular expression of the underlying composition, produced and recorded by the recording artist.

Publishers vary in size: some are small, independent boutique firms and some are branches of multinational corporations.

Music publishers offer a variety of services. Typically, they are responsible for securing the placement of songs in the publisher’s catalogue where royalties and other revenue will be generated. These revenue streams range from royalties obtained through the licensing of compositions for the purposes of sound recording, to digital streaming and synchronization in film, commercials, or television.

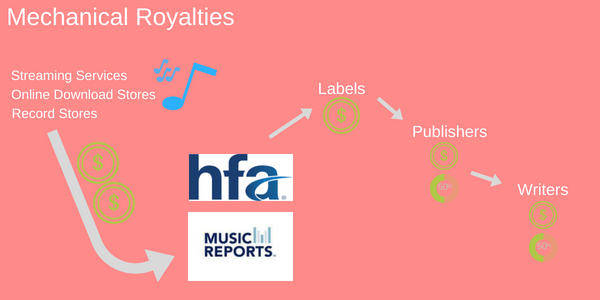

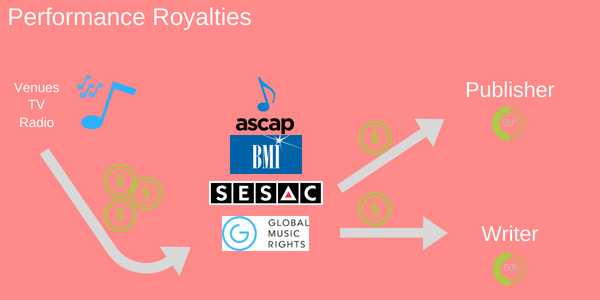

Publishers interact regularly with collection agencies such as the Mechanical Licensing Collective, Harry Fox Agency and Music Reports for mechanicals, and ASCAP, BMI, and SESAC for performances in order to properly collect royalties. Typically, record labels maintain close relationships with music publishers, as publishers control the compositions being recorded by the artists signed to their rosters.

Background

The history of music publishing in America is intertwined with various technological developments that happened over the course of the 19th and 20th centuries.

In the mid-1800s, songwriters had their compositions printed in bulk by businesses who owned printing presses. Some of these companies began selling sheet music to the masses and evolved into music publishers. These businesses largely exploited songwriters until advocacy groups like the National Music Publishers Association and the Music Publishers Association in Britain were established. As a result, global copyright law was strengthened and songwriters were better protected.

The development of player pianos and piano rolls in the early 1900s helped spur the writing of the 1909 Copyright Act. In addition to extending the duration of copyright (length of time that works are legally protected) and offering protection for performances, this legislation provided protection for the reproduction of compositions and in essence created the mechanical right and royalty. Mechanical royalties would come to extend beyond piano rolls to include phonorecords when they started to be used in commerce.

In 1914, composers banded together to create ASCAP, which was an entity designed to collect and distribute royalties from the performances of compositions. ASCAP was the first performing rights organization (PRO) in the US. Since their business model was to act as an intermediary between performance venues and music publishers, ASCAP became an important force in the industry. The advent of radio and television made royalties for public performances a primary source of revenue for music publishers.

New York City’s Tin Pan Alley became a hub for music publishing in the first half of the 20th century. It was here that song-pluggers pitched songs to performers in vaudeville and theater venues and the companies sold copies of sheet music in mass. When ASCAP’s competitor, BMI, was formed in 1939, the first major music publisher in Nashville was born. Acuff-Rose was affiliated with BMI, and signed major country acts like Hank WIlliams, Roy Orbison, The Everly Brothers, and Don Gibson.

Today’s publishing industry is dominated by large companies like Sony/ATV, Warner/Chappell, Universal Music Publishing Group, Kobalt, and BMG. There are, however, hundreds of other independent music publishers who collectively account for around 19% of industry market share. There are also many more musicians creating and distributing their music independently using administration services like CD Baby, Tunecore, and Distrokid.

The Publishing Deal

Songwriters sign publishing deals for a variety of reasons, and the types of deals they can sign are multifaceted. A publishing deal can give the writer’s songs a pipeline to being recorded by a successful artist, and can provide them with other avenues to get their compositions out into the world where they might be monetized. Furthermore, collection agencies like the HFA and ASCAP aren’t incentivized to distribute royalties to particular songwriters. Instead, these agencies are focused on collecting royalties from music users rather than making sure songwriters receive the royalties that are rightfully theirs. That’s where deals with publishing entities come in. A publisher courts songwriters to sign deals because they want to have as many hit songs in their catalogue as possible, and signing on the best writers as clients gives them the best chance at doing so.And, songwriters want to receive the maximum amount of royalties from their hit songs. However, in the modern music industry, many more musicians write, record, and distribute their own music without intermediaries. As a result, the traditional model is starting to change.

The 50/50 Split (Full Publishing)

One of the most important things to know about the licensing of compositions is the industry standard in place for royalties. Regardless of what type of publishing deal is agreed upon, the writer and the publisher split royalties 50/50 per copyright law. The chain of royalties is as follows:

- Performing Rights Organizations (PROs) and collection agencies like the Mechanical Licensing Collective, The Harry Fox Agency and Music Reports collect royalties from performances, mechanicals, etc.

- The PROs and agencies then pay royalties to the publisher and songwriters.

- The publisher pays the writer half of the royalties and keeps the other half in the case of mechanicals

- OR the publisher keeps its share of performance royalties because the PROs pay writers their share directly.

Individual Song Agreement

In this deal, the writer agrees to transfer ownership of the copyrights to songs that already exist to a publisher. This agreement can encompass any number of songs, ranging from a single song to an entire catalogue.

For instance, Sony/ATV owns copyrights of songs written by Bob Dylan, Lady Gaga, Taylor Swift, Willie Nelson and many more. The company recently sold many Bruce Springsteen works to Universal Music Publishing Group (UMPG), making Universal the sole publisher of all Springsteen’s works.

Exclusive Songwriting

An exclusive songwriting deal is an agreement in which the songwriter pledges to write a specific number of songs in a specific time period, all the applicable copyrights of which will be transferred to the publisher. As suggested by the name, these deals are exclusive, meaning that a writer is also promising to work only with the publisher in question for the duration of the agreement.

For example, a writer may sign on to write (or co-write) 10-20 songs per year for the publisher, with an option to extend the time span. The popularity of exclusive songwriting deals is dwindling as the publishing industry begins to stray from traditional methods.

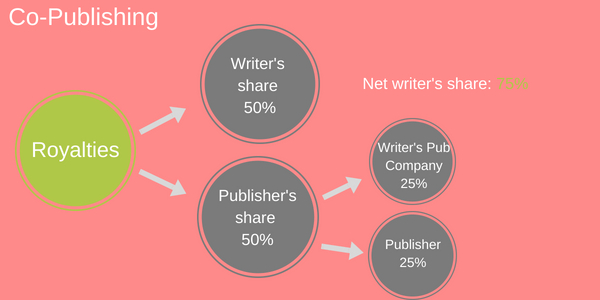

Co-publishing

A co-publishing agreement means that while the music publisher receives ownership equity in the copyright and administers its exploitation, another publisher (possibly a songwriter’s own company) controls the other piece of the publisher’s share of ownership. This type of agreement often happens when established songwriters who have a lot of power within the industry sign up to work with a publisher. The deal gives the songwriter more leverage and money, because while the writer still gets the 50% writer’s share, their publishing entity (or whomever’s) also gets a piece of the 50% publishing share.

Work For Hire

There are exceptions to the standard 50/50 royalty split rule discussed earlier. One of these exceptions occurs when a songwriter signs a work-for-hire contract. Under these deals, the publishing company fully owns the songs written by the writer in accordance with the deal. The company is listed as the writer of the work, not the actual writer. In these instances, writers do not have any of the rights traditionally given to any creator of intellectual property. This includes the right of first use. The writer of the song will usually be paid an up-front or one-time dollar amount for the work done under the contract. When faced with the opportunity to sign a publishing deal, it is critical to note whether that deal is work-for-hire. For works made for hire, the duration of time of the copyright is 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever comes first.

*An important note

In many publishing deal contracts, there is work-for-hire language. But in practice, it may not seem like the publisher regards themselves as the sole owner of the work. The purpose of this language is to extend the copyright duration and to counteract the termination rights of the original writer (see our songwriter guide for more on terminations). It is important for any writer signing a publishing deal to be aware of work for hire clauses and to make clear what the terms of the deal will look like in practice.

Admin

In administration deals, the songwriter retains full ownership of their copyrights. Though the publisher does not have any ownership in the work, the duties of the publisher remain the same. Instead of taking royalties generated from copyright ownership, the publisher takes a percentage off the top of the song’s earnings as overhead. The percentage taken from earnings is usually between 10% and 25%. These agreements are becoming more and more common, as the traditional songwriter deals become less viable for the average writer.

While some deals involve only Administration services, all publishing deals contain some type of administration language because this is the basic service of a music publisher.

360 Deals and Label Services

360 Deals are agreements in which a publisher provides more services than is standard. By doing so, the publisher becomes involved in nearly every aspect of the musician’s business. The services provided can extend to any aspect of their career. Most often, they include management, recording, touring, merchandising, endorsements, and other miscellaneous aspects of the songwriter’s business.

These deals benefit publishers by allowing them to have some stake in everything the musician is doing -- including all of their revenue streams. This means a higher chance of profit for the publisher. These deals can also benefit musicians by offering an opportunity to have a sort of one-stop-shop for all of their business needs. Many large publishers such as BMG and Kobalt now offer “record label services,” and have signed songwriters as recording artists to their rosters. The musicians sign these deals in lieu of a record contract with a label or traditional publishing deal.

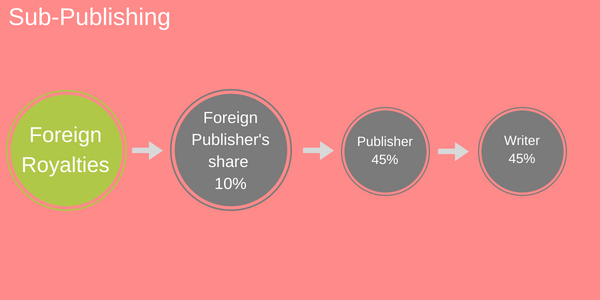

Sub-Publishing

A sub-publishing deal simply means that the publisher designates a subsidiary company to administer and license copyrights from their writers in a foreign market. Foreign music publishers can sub-publish American music and vice versa. Usually these deals are done company-to-company. For example, Universal Music Publishing Group (UMPG) recently signed a sub-publishing deal with Disney Music Publishing. Disney owns 34 different music publishing companies around the world, and UMPG has effectively outsourced licensing and collecting duties to some of these subsidiaries. Likewise, a very small publisher in the US may sign a sub-publishing deal with one of the majors to cover administration in foreign territories.

Important Deal Points

The Term

The term in a publishing deal establishes the duration of the contractual obligation. This can be measured in years, but can also be measured by the number of songs or records agreed upon, advance recoupment, or any other bench marks the publisher and writer agree upon. At the end of the term, the publisher typically still has ownership in the copyright unless there is specific language in the contract reverting full ownership back to the songwriter. Reversion clauses and termination doctrine can get very complicated, and will be detailed in a separate guide.

Advances

Advances are payments given upfront to the writer, prior to that writer carrying out specific tenets of the publishing agreement. This money can be paid to the writer on a weekly, monthly or yearly basis, and is repaid through the royalties generated by their compositions. In the music business, this means it is recoupable. Advances are NOT free money; the publisher recoups this income by taking royalties from the songs. For example, let’s say a writer is signed to a one year, 12 song agreement, and receives a $20,000 advance for the year. At the end of the year, the grand total sum that the song has earned is $24,000. The publisher will recoup their entire $20,000 they gave the writer at the beginning, leaving the writer with only $4,000 in real income.

Importantly, advances are only recouped with royalties. This means that, if the writer hasn’t recouped at the end of the term, the publisher will typically either extend the term or determine some other way to make the money back via licensing the song. The writer is NOT required to pay back the money advanced to them out of pocket.

Minimum Song Delivery Requirements

In exclusive songwriting agreements, perhaps the most important tenet of the deal is the clause enumerating how many compositions a writer must produce in a given amount of time. These terms can vary; some contracts may have a duration relating to when a song can be commercially available, while some may have no specification on that front at all.

A few possibilities:

10 songs written solely by the writer within a calendar year (this excludes co-written works)

20 songs in which the writer has at 50% ownership. This means that they can co-write with others as long as they own 50% of each song.

Controlled Composition Clauses

A separate issue that affects publishers and songwriters is the controlled composition clause in an artist recording agreement. These clauses affect publishers when the artist is also the songwriter, which is fairly common. Essentially, controlled composition clauses are placed in recording contracts to place a limit on how much a record label is required to pay an artist/songwriter for their controlled composition. This limit, in turn, can also impact the revenue streams that publishers split with writers. It’s important to note that controlled composition clauses can affect whole songs, so that if the artist/writer only has 50% interest in a controlled composition, then per some agreements the controlled composition clause can affect the royalties for the co-writer who is not a party to the artist agreement.

What a Publisher Does

Once a publisher signs deals, adds writers to their roster, and amasses a catalogue of copyrights, there are many things the business does to generate revenue. Since the licensing of songs is intimately tied to the specific rights conferred upon an owner in copyright, here is a refresher on those six exclusive rights:

- The right to reproduce the work (as in a physical record).

- The right to create a derivative work, meaning an adapted work that is directly based on the copyrighted work (for example, creating a movie based upon the compositional elements of a song).

- The right to publicly distribute copies of the copyrighted work (for example, distributing music so as to be available on streaming services).

- The right to publicly perform the work (for instance, terrestrial radio airplay).

- The right to publicly display the artistic work.

- For sound recordings: the right to publicly perform the recording through digital audio transmission (not applicable to compositions).

Licensing and Administration

Perhaps the most fundamental piece of a publisher’s business is the licensing of songs, and the administrative upkeep of the things that happen as a result of that licensing.

Types of Licenses

Mechanical

The publishing company issues a mechanical license to a record label or any party who wishes to copy the composition in the form of a physical, permanent recording (the technical term is “phonorecord”). It is important to note that this also includes permanent downloads (like songs purchased on iTunes) as well as interactive streams. From these licenses, mechanical royalties are accrued. The amount of royalties depends on a fixed rate determined by the Copyright Royalty Board The current rate is 9.1 cents per copy sold. Typically, the user of the end product (say, a record store that sells records to consumers) gives 9.1 cents for every non-digital phonorecord delivery, non-interactive transmission, and transmission of works accompanying a motion picture or other audiovisual work. For digital phonorecord delivery of a musical work, a user must purchase a blanket license from the Mechanical Licensing Collective, which will then pass royalties on to composition owners. These royalties are often returned to the publisher who splits the payments with the writer. It is important to note that these royalties are distinct from recording artist royalties. Those are the payments a recording artist receives from the sale of their recording, and they are determined by the recording agreement. Mechanical royalties, on the other hand, end up solely in the hands of writers and publishers.

Performance

Traditionally, performance income accounted for the bulk of a publisher’s revenue, and this was due to the immense amounts of money a terrestrial radio hit or broadcast TV placement could generate. The PROs, ASCAP, BMI, SESAC (and now GMR) collect performance royalties from broadcast entities such as terrestrial radio, TV stations, non-interactive streaming services like Pandora and Sirius XM, and performance venues and distribute them to publishers and writers.

The most common type of licenses that PROs offer to users are “blanket licenses,” which give the licensee access to the PRO’s whole catalogue of compositions. Accordingly, the PROs pay royalties back to writers and publishers using a weighted percentage system based on the type of performance from which the royalties are generated. Songwriters and publishers are paid separately, regardless of whether the songwriter is affiliated with a publisher. Once the dollar amount is determined, ASCAP sends a check to the individual writer for 50% of the amount, and a different check with the same amount to the writer’s publisher.

An example:

ASCAP uses a number of factors to come up with “credits” for all the performances of a given writer’s work. The PRO divides the total dollar amount in license fees they have accrued by the number of credits for a certain writer to determine their royalty payout. The credits are based upon the type of use (i.e. big radio station play vs. local TV commercial spot) and the number of uses (one-time broadcast vs. six-month syndication), in addition to a few other factors.

Synchronization

Synchronization (sync) licenses are conferred when a composition is to be used in tandem with an audiovisual work, like in a film, TV show, commercial, or any time music is synchronized to a visual image. These are in paid for in one-time fees. However, if the work is used in a broadcast medium like television, the work will also generate performance royalties. Publishers typically have a department dedicated to securing and negotiating sync placements for compositions in their catalogues. Music supervision companies are intermediaries between production companies and music publishers. Supervisors are typically responsible for providing licensed songs to use in the audiovisual works. For example, a production company producing a major-budget film in Hollywood will hire a music supervision company to fill certain spots in the film where music is needed. The supervision companies in turn work with the record labels and publishers who own the rights to the works in order to secure licenses. In an age where audiovisual content is blossoming and being consumed widely on the internet, synchronization is an integral part of the publisher’s business.

An important note:

Those wishing to use music in an audiovisual work must also obtain a master-use license from the owner of the sound recording, which is typically a record label. This includes any type of use in film, TV, and any other visual media.

Adaptations/Translations

Remixes, new arrangements, and other derivative uses require an adaptation license. This does not include the minimal changes necessary to record a composition that has already been recorded. Adaptations usually do NOT create a new copyright for a song and adaptors typically do NOT get a percentage as writer or publisher. Adaptors and translators may be listed on the songwriter credits for their role.

Print

A print license gives the licensee the ability to use the composition as a sheet music product, on merchandise, or elsewhere.

Grand Rights

If the publisher wants to license music to a theater production company for use in a dramatic work like a musical, grand rights are implied. These are separate, one-off contracts and usually involve some sort of adaptation license and approvals of how the compositions are used in the production.

Catalogue acquisition

A large part of the publisher’s business is the buying and selling of catalogues, which are collections of works by one or a group of writers. Usually, acquisitions of catalogues take the form of one publishing company legally acquiring another publishing company, and thus obtaining the rights to all the songs. The purchase price is usually a financial calculation based on a multiple of average annual net earnings in recent years. For example, Sony ATV recently made a bid to purchase 60% of EMI music publishing to the tune of $2.3 billion. Catalogues full of hits are incredibly valuable assets, because the owner (typically a music publisher) can essentially sit on them, do nothing, and still make large sums of money.

Hit Songs

The value of a publishing catalogue has traditionally been defined primarily by its number of hit songs. Whether a song is a hit is determined by its place on the charts. These charts are made by trade publications like Billboard Magazine and radio monitoring services like Mediabase. Today, these traditional institutions are becoming less relevant, and other charts are taking their places. When digital downloads were prevalent in the mid-2000s, the iTunes charts became an important measure of a song’s popularity. And today, Spotify has charts that track global streams and curated playlists that can help break an artist. Billboard has over time augmented their reports to include important formats such as YouTube views and streams from other platforms. As such, Billboard remains a gold standard in music charting.

Here are some examples of songs measured as hits in non-conventional ways:

PSY’s “Gangnam Style” on YouTube

Drake’s “One Dance” surpasses 1 billion Spotify streams

Post Malone racks up Soundcloud streams, signs record deal

Neighboring Rights and Foreign Royalty Collection

Publishers work with foreign companies and PROs pursuant to sub-publishing deals to properly administer royalties accrued in foreign markets.

Legal Affairs

If a publisher does not have in-house counsel, they still use the legal services of attorneys extensively. Every deal made requires the work of a transactional attorney, and publishers often make legal claims to works and pursue litigation involving anything from straightforward copyright infringement to royalty and catalogue issues.

The Creative Department

Virtually every traditional music publishing company has a “creative department,” which is responsible for the more qualitative aspects of the business—essentially, finding and promoting the best music.

A&R, Song Plugging, and Promotion

Short for Artists and Repertoire, A&R personnel are responsible for finding new writers to sign, or new catalogues to purchase. The goal of A&R personnel is to maximize the revenue of their artists. These are the people who attend writers rounds and showcases, and develop relationships with a wide array of rights holders and industry stakeholders. A&R will also help to develop relationships between songwriters, and in some genres, relationships between producers and writers. The focus of A&R personnel varies drastically depending on what kind of artists they are responsible for. For example, the A&R for a producer is significantly more focused on the success of an underlying composition as that’s where the producer will obtain a majority of their royalties. Conversely, an A&R for a recording artist is more concerned with the success of the sound recording, as the sound recording is what generates a majority of the revenue for the recording artist and their label.

Song-Pluggers are people who have relationships with recording artists, record labels, producers, and who try to pitch songs to be “cut” on a recording. It is important to note that there may not be specific job titles or labels for these types of jobs; one person can do many things in the process of getting a song recorded, and it usually depends on what sorts of relationships within the business that person has.

Demos

Personnel in the creative department are also responsible for producing demo recordings, which are used to pitch the songs to licensees. These personnel can be actively engaged in the creative process, or can be hands-off. It depends on the company, writer, and type of deal.

Artist and Writer Development

Development is a vague term used to describe anything from aiding the writer/artist in their creative writing or performing skills, to the crafting of their artistic persona, personal brand, and self-promotion strategy.

An important note:

It is now common for the lines between songwriter/artist and publisher/record label to blur. Demos can be mastered and used in commerce as recordings, and companies who have traditionally operated under publishing models can and do provide label services. These days, there are less traditional “publishers” and “labels,” and more “music companies” who offer a broad range of services to the musicians on their rosters.

Different Kinds of Publishers

There are several different kinds of Music Publishers. The categories largely mirror those of Record Labels.

- Major: These are the Music Publishers associated with the three largest Record

- Labels: Sony BMG, Universal Music Group, and Warner Music Group.

- Major Affiliated: Independent Publishing companies that are associated with majors who help handle some of their responsibilities

- Independent: Self-funded with no major affiliation

- Writer-Publishers: Some songwriters handle their own publishing or hire independent contractors and pay them directly rather than through royalty fees

A short list of publishers

Sony ATV

Warner-Chappell

Universal Music Publishing Group

BMG

Kobalt

Downtown

Round Hill

SONGS

Imagem

Wixen

Black River

Words & Music

ABKCO

Ole

Big Deal

Peermusic

Here is a comprehensive list of music publishers in the US, Canada, and the UK from Songwriter Universe.

Advocacy Groups

Publishers have often taken a back seat to record labels in terms of licensing procedures and legislation. These are groups who represent the interests of publishers and songwriters, and who lobby, educate, and campaign on their behalf.

NMPA

AIMP

MPA

Future of Music Coalition

NSAI

Sources:

https://www.copyright.gov/history/1909act.pdf

https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/8454566/publishers-quarterly-top-ten-sony-atv-warner-chappell-universal

https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/7882127/bruce-springsteen-universal-music-publishing-worldwide-deal

https://www.bmi.com/news/entry/Foreign_Sub-Publishing_Income

https://variety.com/2018/music/global/universal-music-publishing-group-disney-music-publishing-territories-1202664897/

https://secure.harryfox.com/public/userfiles/file/PressReleases/HFARoyaltyRatePR10-2-08.pdf

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/106

https://soundcharts.com/blog/how-the-music-publishing-works

https://www.thebalancecareers.com/what-does-a-music-publishing-company-do-2460915

https://stem.is/music-publishing-101/

Composed by

Will Donohue, Luke Evans, Mamie Davis, Jacob Wunderlich, Rene Merideth, & Aaron Davis

Want to use this guide for something other than personal reading? Good news: you can, as long as your use isn’t commercial and you give Exploration credit.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.