Why we wrote this guide

The purpose of this guide is to provide a detailed account of what a composition is and to further elucidate the difference between the composition and the sound recording. This guide will build a foundation that will aid in one’s understanding of the complex web of music industry licensing structures and business entities covered in the overall guide.

Who this guide is for

- Composers or Songwriters seeking a thorough understanding of their rights as creators. In this guide, they will also have the opportunity to learn how to maximize the potential of their work(s) in order to target key audiences and increase profitability - all while staying true to their craft.

- Music publishers who want to brush up on the nuts and bolts of their business and who are looking for what makes a composition “the best” in order to maximize investments and increase income flow.

- Those interested in a career in music publishing or or the music business in general.

- Music enthusiasts who want to write music (or just learn about it) but don’t know where to start.

Contents

Read time - ~ 30 minutes

One will also find links to tools and additional resources that can be utilized to further one’s education and get the most from the network.

Finally, as questions and ideas arise, please do not hesitate to reach out to Exploration for clarification. We are here to help.

Table of Contents

Overview

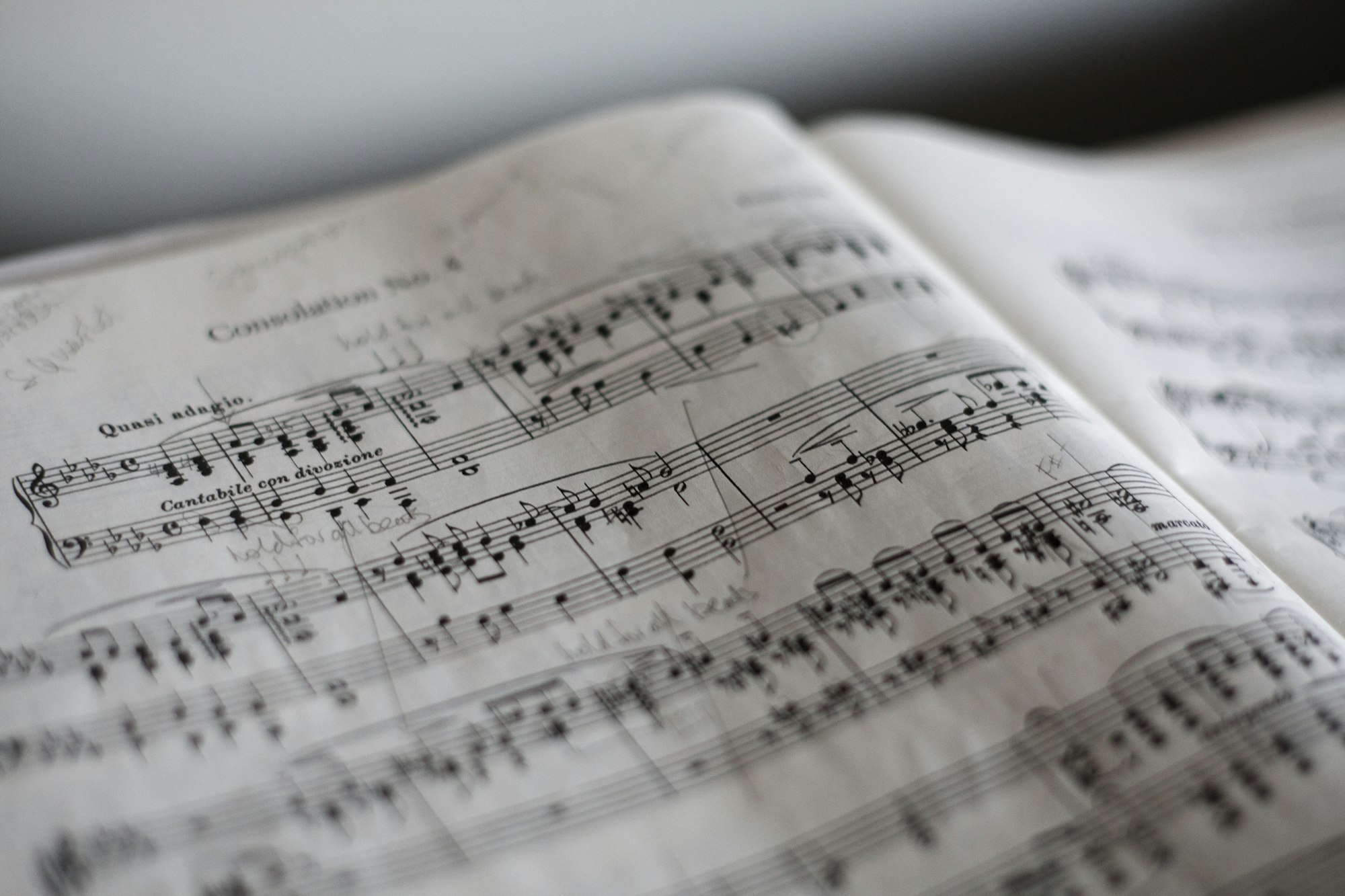

It is the collection of notes, melodies, phrases, rhythms, lyrics, and/or harmonies that make up the essence of the work. The term “composition” typically refers to an instrumental musical piece, while the term “song” usually applies to musical works accompanied by lyrics. Though the two terms technically refer to different things, they will be used somewhat interchangeably in this guide because they function in the exact same way in the music business.

There is no concrete definition of a composition, only the aforementioned terms we use to characterize it. However, there are criteria that a composition must meet in order to be protected under American copyright law. The song must be fixed in a tangible medium (such as notes written on a sheet of paper or a sound recording on tape or in a digital file) and must be an original expression. Once these requirements are met, compositions can be licensed to interested buyers through a music publisher. It is important to note that this process is independent from that of the licensing of sound recordings, which are separate copyrights created by artists and are usually owned by record labels.

Background

The history of composition is much too abundant to fully recount in detail here. However, it is important for the songwriter to have an understanding of how songs and compositions came to be and evolved to become the foundation of the modern music industry.

A brief history of the Western composition

Archaeologists date the existence of music back to between 60,000 and 30,000 BC. This, however, was only the beginning of the prehistoric era of music, meaning that there is no written record of these civilizations and their music. Codification of music began when songs and anthologies could be recorded on paper and collected.

The first known practice of saving and formally notating musical creations is by the Catholic Church in the 9th and 10th centuries. During that time, the church began using simple unaccompanied vocal parts called Gregorian Chants (named after Pope Gregory I) as a fundamental part of their practices and services. Due to the prominent role of the Catholic Church in the Middle Ages, Gregorian Chants became the first compositions to be consumed by the masses.

While sacred music continued to gain relevance and expand, travelling musicians performed and popularized secular music. By the 14th century, society began to grow apart from the church. In turn, secular music began to outgrow sacred music. In 1440, the invention of the printing press catapulted the art of composition into a rapid period of growth. The invention allowed the mass-production of sheet music, which made compositions more of a commodity.

In the 16th century, composers began to orient their songs around one tone or key. This concept is called tonality and it remains a key part of compositions today. A century and a half later, Western society shied away from the idea that music is a divine art as the masses began to view it as a form of performance art meant to entertain. The new accessibility to music caused compositions to become a much larger part of culture.

The 20th century witnessed the advent of many new musical genres: big band, blues, jazz, and singer-songwriter, to name a few. The legal system in the United States found itself unprepared to handle the rapid growth of the music industry. Congress accommodated the rapid changes with the 1909 Copyright Act and the formation of the first performing rights organization, ASCAP, in 1915. These events were the first real attempts to protect the rights of composers and to ensure that they were being compensated for their intellectual contributions.

Before the 1960s, songwriters and artists played different roles in the industry: songwriters wrote songs and artists recorded them. But in this decade, the lines between these two positions began to fade. The “singer-songwriter” played a major role in changing the art of composition as composers were now writing for themselves rather than for other artists. This trend is still prevalent in today’s industry. The typical singer-songwriter’s style of composing was far less focused on technical training and music theory, which opened the door for many more composers to begin creating.

Today, there are more ways to compose than ever before. Through the use of pre-made sounds, loops, samples, MIDI keyboards, and effects, composers can create songs entirely electronically. This creates an intriguing new predicament in differentiating sound recordings from compositions, as it is not uncommon for these compositions to live only inside the recording in lieu of sheet music. However, even if a song is only created using electronic recording tools without any live instruments, a composition copyright still exists.

Copyright Fundamentals

An original composition is an intellectual property protected under copyright law. A composer, or other owner if rights have been transferred, is given exclusive rights to control and exploit their works for a certain period of time. While copyright protects many different types of compositions such as literary, dramatic and poetic works, this guide focuses on musical works.

Section 102 (a) (2) of the Copyright Act specifies that “musical works, including any accompanying words,” qualify for protection. The term “musical works” includes songs with music and lyrics as well as the notes, rhythms, melodies, chords, and arrangements of instrumental compositions. In the case of a musical composition that includes both music and lyrics, a copyright will protect the combination of music and lyrics, the music alone, and/or the lyrics alone. In order to be protected by copyright, musical compositions must be original, contain expression, and be fixed in tangible form.

Here is a little more on the three requirements for copyright protection:

-

Originality

- This is a completely subjective requirement, as it can be argued that nothing is truly original. The bar for originality, however, is quite low in copyright doctrine. The work must simply be created independently; it can’t be a copy of another work. The work doesn’t have to be unique (think about how many songs employ the I V VI IV chord progression), it must simply be the songwriter’s own creation.

-

Expression

- This requirement deals with the notion that copyright doesn’t protect ideas. In other words, the mere idea of “a song about a boy and a girl traveling across the country together” isn’t protectable in the slightest. If the composer writes down lyrics and tells an original story, however, then they’ve created a protected work.

-

Fixation

- This is perhaps the most important requirement. In order for a composition to be protected, it must be “fixed in a tangible medium.” In other words, there needs to be a physical manifestation of the work - it can’t simply be in the writer’s head. In the case of a composition, this physical embodiment can take the form of sheet music, or a Word document on the computer. It can even be in a sound recording. In that case, there would exist both a sound recording and composition copyright, both embodied by whatever medium in which the recording exists (like a CD or MP3 file).

Once the song has met these three requirements, the songwriter is able to license their work and make money. Copyright protection affords the composer six exclusive rights which roughly correspond to various licensing processes and revenue streams. These rights, as outlined in Section 106 of the Copyright Act, are as follows:

- The right to reproduce the work

- The right to create a derivative work, meaning an adapted work that is directly based on the copyrighted work

- The right to publicly distribute copies of the copyrighted work through sale or for free

- The right to publicly perform the artistic work

- The right to publicly display the artistic work

- For sound recordings: the right to publicly perform the recording through digital audio transmission (not applicable to compositions)

Upon the creation of a composition, the above rights exclusively belong to the songwriter(s), who owns the copyright. No one can use the work in any of the above ways unless they obtain a license to do so from the copyright owner. The work does not have to be registered with the Copyright Office, although doing so gives the owner certain benefits in the event of a legal dispute over ownership.

An exception:

Compulsory mechanical licenses give licensees the right to reproduce and distribute a work. For example, the mechanical license gives a recording artist the right to record the song (reproduce), and the artist’s label the right to sell that recording to digital platforms and record stores (distribute). “Compulsory” here means that the copyright owner cannot refuse the license if it is requested. The hypothetical licensee simply has to give a Notice of Intention (NOI) to the copyright owner and subsequently pay them a statutory mechanical royalty* of 9.1 cents per copy. After this, the licensee can record the song and distribute those recordings.

Though NOIs historically authorized all compulsory licenses, they no longer apply to digital delivery of musical works (i.e. permanent download, limited downloads, or interactive streams). Under the 2018 Music Modernization Act, NOIs only authorize non-digital phonorecord delivery (i.e. compact disk, cassette, or vinyl). As of January 1, 2020, the Copyright Office no longer accepts NOIs to obtain a compulsory license for making a digital phonorecord delivery of a musical work. Rather, users may obtain compulsory authorization through the purchase of a blanket license covering all musical works available for compulsory licensing. Such a license is made available through the Mechanical Licensing Collective (MLC).

To obtain a compulsory mechanical license, it is important to comply with all provisions of Section 115 of the Copyright Act as well as the regulations set in place by the USCO.

With the ubiquity of the internet and digital technology, there are more ways for people to distribute their creative works than ever before and more ways for users to access them. It is thus incumbent upon the songwriter or composer to keep track of the ways in which their works are being used, because these uses can often, by law, generate royalties.

- The statutory mechanical royalty is a rate determined by an arm of the USCO called the Copyright Royalty Board. Although the rate has changed throughout history, the current rate was set in 2006.

Registering a copyrighted work

Registering copyrights with the US Copyright Office (USCO), although not mandatory, is a common procedure for those in the business of licensing music. While it is a formality, it gives the writer certain benefits:

- A way to prove prima facie (a legal term for “on the face of it”) that they are the owner of a copyright

- The ability to file an infringement claim in federal court

- When registered within three months of publication, the owner is eligible for statutory damages and attorneys’ fees

- Registration permits a copyright owner to establish a record with the U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) for protection against the importation of infringing copies

Registration is not only a tool with which to bolster an infringement claim. The USCO’s registry can also help writers get paid. When a digital platform such as Spotify or Apple Music streams a song, they must by law report the use under the rules of a compulsory mechanical license. However, the platform is allowed to search the records of the Copyright Office. If they cannot find an owner, they can report this to the Copyright Office and are then not responsible for the license nor payment on those streams they've reported this way. Thus, if a work is not registered with the USCO, there is a chance that the work could be accruing unaccounted-for mechanical royalties which are simply being pocketed by streaming services or held in escrow.

One can register a copyright online for a small fee of $35-45, and must also deposit a nonrefundable copy of the work claimed.

Our team at Exploration has written and published a guide to Copyright Registration that breaks down the process into detailed steps. Click here to read the guide.

Additional Reading:

- Click here for more detailed information on the registration process

- Click here to register a work through the USCO’s online registration portal

The public domain and duration of copyright

For most works created after January 1st, 1978, the duration of copyright is the life of the last living author plus 70 years (copyrights are posthumously inherited by descendants or other rights claimants).* After this span of time, however long it may be, the composition enters the public domain-- making it free to use by anyone without obtaining a license or paying royalties. For example, anyone is completely free to use the compositional elements of “Yankee Doodle” in any way one pleases. Even if two artists release their new recordings of the song, they cannot sue each other because the composition has already entered the public domain. Currently, any composition proven to be written before 1923 is in the American public domain. Per the Sonny Bono Act of 1998, a new group of intellectual properties entered the public domain on January 1, 2019, and will continue annually until 2073. To access a free database of American folk tunes in the public domain, click here.

- For works made for hire or works with anonymous or pseudonymous authors, the duration is 95 years from publication of 120 years from creation, whichever is shorter. For more information on copyright duration, click here.

Joint works

Songs are often created by more than one composer and thus copyright ownership can be split between multiple people or business entities. One may own the copyrights to just a song’s lyrics, or just a song’s melody. One could also own half the lyrics and none of the melody. It all depends on how the composers agree to split up ownership. In the absence of a written agreement, ownership is split evenly between each contributing composer.

In some genres, it is common for songwriting credits to include individuals that played no role in the writing process. For instance, a record producer may negotiate a share of songwriting ownership, even though that producer may not have technically “written” the song. Other times, an acclaimed recording artist may negotiate songwriting ownership in exchange for recording the song, if it is likely to be a hit solely by virtue of that artist recording it.

Covers and arrangements

The distinction between a cover and an arrangement of a given work can be confusing. A cover refers to the performance of a copyrighted work that does not substantially change the compositional elements of the original song. For instance, when Eric Clapton covered Bob Marley’s “I Shot the Sheriff,” the underlying compositional elements such as the chord structure, bass line, melody and harmony stayed the same, though it was performed differently.

Conversely, an arrangement will often contain added notes and embellishment, and perhaps different, more, or less instrumentation. For example, one could “arrange” a Bach Cello Suite for the classical guitar, or arrange Duke Ellington’s “In a Sentimental Mood” for a jazz quartet instead of a big band.

Essentially, a cover only changes the original composition as much as necessary for a new artist to perform it. An arrangement purposely changes the original song to create a derivative work.

Note that it is perfectly legal to perform a cover of a song, so long as the venue or platform has the proper blanket license from whatever performing rights organization the writer(s) of the original is affiliated with. When an artist licenses the rights to perform or record a cover, it is generally understood that they have the rights to make minor adjustments as necessary to fit their style and instrumentation. However, this is not deemed to be a new arrangement. A new arrangement creates much more purposeful, large changes to the original composition for the purpose of creating a secondary work from it, rather than simply to change it as needed for personalization. Arrangements can create new copyrights if they are created based upon public domain works, because they create a new work from them. New arrangements also create new copyrights to a derivative work.

Thus, in order to perform an adapted work, such as in the case of an orchestral arrangement in a concerto, one must obtain both a performance and an adaptation license.

Making Money

Though explaining how your compositions should and will make you money is more thoroughly explained in the guides for songwriters and music publishers, it is worth briefly discussing how compositions fit into the overall business of music, namely the integral role of composition licensing. The licensing of compositions plays an integral role.

Essentially, songwriters compose songs and assign them to publishers through publishing deals and agreements. Publishers in turn license those songs to music users across the world, users such as record labels and film and TV companies. The publishing companies accrue royalties from the use of these songs, which they split with the songwriter.

On the other hand, artists record sound recordings and assign those copyrights to record labels, who market and distribute the recordings across the world.

The distinction between these two copyrights is critical if one is to understand all the inner workings of the industry.

In the marketplace, there are many ways in which a composition can create income for its creator. Here are just a few:

- Performance royalties from PROs for performances on radio, via stream, in a live concert venue, and in other places such as restaurants and retail stores

- Mechanical royalties from the sale of copies of records in the form of a physical record, download, or stream

- Synchronization placements in films, TV shows, video games, YouTube videos, and commercials

- “Grand Rights” for the composition to be used in musical theater

- Sheet music sales

- Royalties from derivative adaptations of the song

- Lyrics printed elsewhere - on merchandise, for example

Important metadata

In music licensing, there are many pieces of information attached to each work that help to identify rights holders. This information is called metadata. A songwriter or publisher that is organized and scrupulous in their approach to tracking this data can be more empowered to collect money for the uses of their works. Here are a few different pieces of pertinent information that could accompany a licensed composition:

-

Writer(s)

- The first and last name should be included

-

IPI number corresponding to the writer composer (Interested Party Information)

- The IPI/CAE number is an international identification number assigned to songwriters and publishers by PROs to uniquely identify rights holders.

-

ISWC (International Standard Musical Work Code)

- The ISWC (International Standard Musical Work Code) is a unique, permanent and internationally recognized reference number for the identification of musical works.

-

HFA Code

- 6-character unique identifier for a song in the Harry Fox Agency database. You can find the song code on a previously issued HFA mechanical license. It is also included in the Songfile information for that song.

-

MRI Code

- Unique identifying number for Music Reports, Inc, an organization that collects and distributes royalties generated by the use of songs on internet streaming services.

-

YouTube Composition Asset ID

-

Territory of Ownership

- The country whose copyright laws the work is subject to

-

Publisher(s)

- If signed to a music publisher, list the name of the company and its address

-

PRO Affiliation

- ASCAP, BMI, SESAC, and GMR are the main performing rights organizations that administer and distribute performance licenses and royalties

Sources:

http://www.kopernik.org.pl/en/exhibitions/archiwum-wystaw/wszystko-gra/muzyka-prehistoryczna/&sa=D&ust=1527791446749000&usg=AFQjCNG6_lIAImhY8oT9yYrvOFIi1EElhQ

http://www.ipl.org/div/mushist/&sa=D&ust=1527606147842000&usg=AFQjCNHwgV_FqAyK3H_QSuvG-wfiONp2eA

http://cmed.faculty.ku.edu/private/classical.html

http://cmed.faculty.ku.edu/private/romantic.html

https://genius.com/3291367&sa=D&ust=1527606147844000&usg=AFQjCNHRzEoPGynzpGbm9aEfNkx0F286HQ

https://www.pdinfo.com/pd-music-genres/pd-popular-songs.php

https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B40sRUnsItocdGRiYmNDeGV6V2M/view

https://www.copyright.gov/registration/

https://www.copyright.gov/title17/

https://www.amazon.com/Music-Copyright-Law-David-Moser/dp/1435459725

https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ15a.pdf

https://www.copyright.gov/licensing/115/noi-instructions.html

https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ73.pdf

Composed by

Luke Evans, Jacob Wunderlich, Mamie Davis, Rene Merideth, & Aaron Davis

Want to use this guide for something other than personal reading? Good news: you can, as long as your use isn’t commercial and you give Exploration credit.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.