Why We Wrote This Guide

This guide serves as a resource to grant interested parties a better understanding of print rights and how they function within the music industry. Print licensing and print royalties from these licenses still provide a significant form of income for interested parties, despite new technology and new revenue streams. According to MusicSpoke, the sheet music industry alone is worth more than $1 billion. Meanwhile, lyric sites on the Internet are collecting massive amounts of ad revenue. In today’s music industry, it is important for songwriters and music publishers to familiarize themselves with the print rights associated with their protected works.

Contents

What is “Printed” Music?

Background / History

What is a Print Right?

What is a Print License?

Print Licenses for the Stage

Securing a Print License

Infringing on Print Copyrights

Exceptions Print Licenses

Royalties for Print Licenses

Term of the Print License

Digital Print Rights

Critical Relationships

Sources

What Is “Printed” Music?

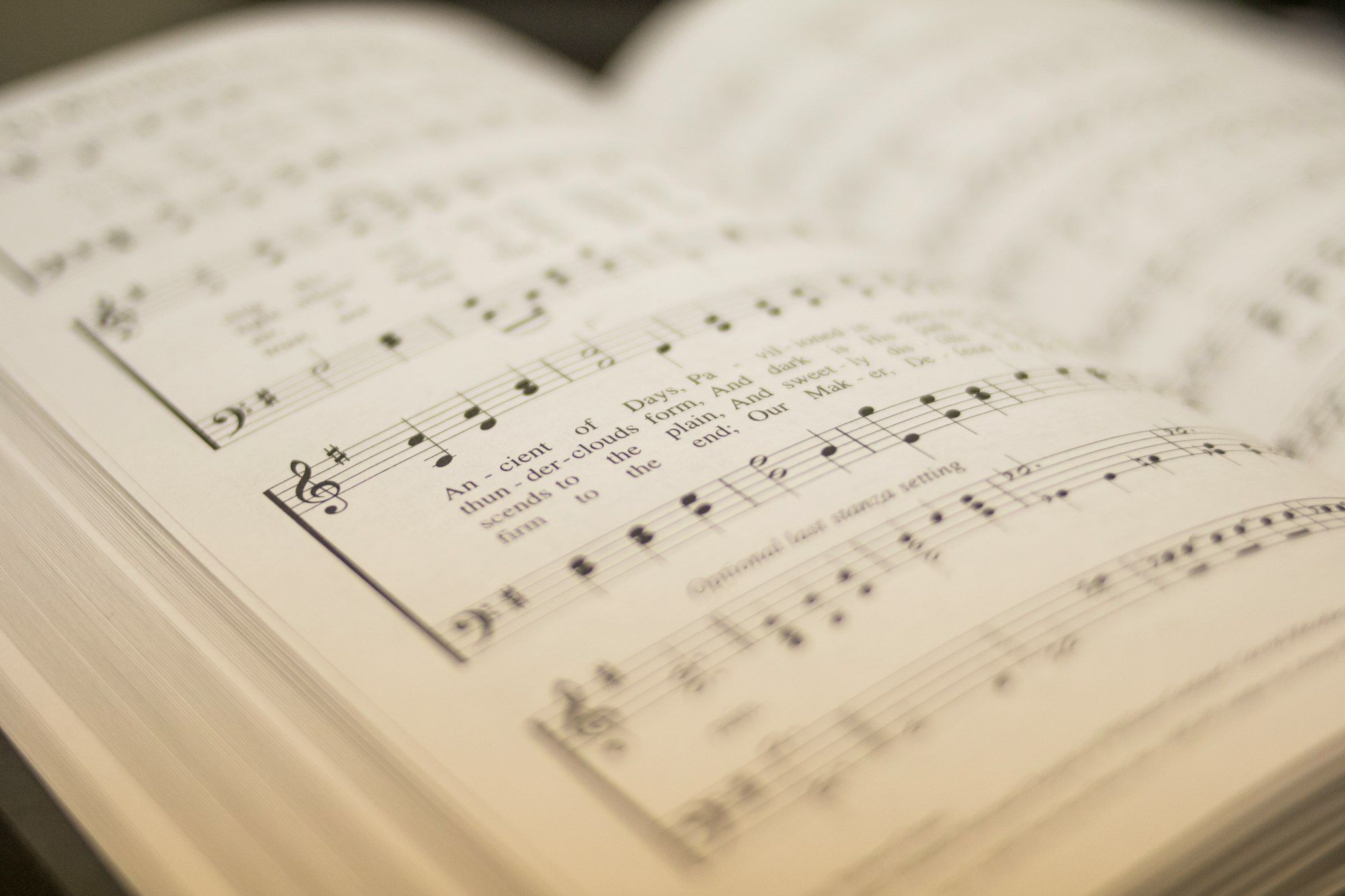

Sheet Music

In most instances, the terms “printed” music or “print rights” are used in reference to sheet music. Sheet music is the printed music of a single song with notes, arrangement, lyrics, chords, and other annotations used by composers to communicate information about the piece of music. Anyone who has taken a formal music lesson can probably visualize this type of printed music: horizontal lines under a series of clefs, dots, time signatures, and other symbols. It's the language every musician—from a symphony violinist to a first-year piano student—uses to “read” music. In the most literal sense, sheet music allows music to be transferred from musician to musician in the most efficient way possible.

Folios

Folios are collections of sheet music for various songs. It is a term for multiple “sheets” of sheet music. An example of this would be a book of sheet music titled Billy Joel Greatest Hits which contains several different songs by the artist in the form of sheet music. A collection of printed sheet music for songs from different artists is called a mixed folio. A matching folio, on the other hand, is a collection of printed sheet music for a particular album, i.e. the folio “matches” the album. A personality folio typically has the picture of the performing artist on it. Using the previous example, Billy Joel Greatest Hits would be considered a personality folio.

Score

The term “score” is used as a common alternative for the term “sheet music.” Several different types of scores exist. A score can refer to sheet music or to music written specifically for a play, musical, opera, ballet, television program, film, or other production. A “film score” refers to original music written specifically to accompany a film.

Background / History

Music publishing did not begin on a large scale until the mid-15th century, when techniques for printing music were first developed. The earliest form of printed music is a set of liturgical chants from around 1465, created not long after the Gutenberg Bible. Prior to this period, music was transcribed by hand, usually by monks and priests hoping to preserve Church music. The few examples of secular music that did exist were commissioned and owned by wealthy noblemen.

Ottaviano Petrucci is widely considered to be the father of modern music printing. In Venice during the 16th century, he obtained a 20-year monopoly from the Italian government to print music. But printing music with moveable type was nearly impossible due to the complex alignment of various elements within the sheet music (e.g. the note head must be correctly aligned with the note staff). Petrucci revolutionized music printing with his triple-impression method, which involved printing the staff lines, words, and notes in three separate impressions. This method created much more legible results.

The influence of printed music was similar to the influence of the printed word: information spread faster, more efficiently, at a lower cost, and to more people than ever before. Throughout the second half of the millenium, this encouraged those who could afford sheet music, i.e. the middle class, to purchase it to perform. As technology continued to improve, so too did the quality of sheet music. Composers could now write, distribute, and sell music for amateur performers, not just professional musicians and Church singers. This in many ways shifted the entire music industry. Unprecedented access to music allowed secular music to rapidly expand.

In the 19th century, the New York City-based group of music publishers, songwriters, and composers known as “Tin Pan Alley” dominated the sheet music publishing industry. Often, publishing houses would print their own versions of popular songs at the time, regardless of whether their songwriter actually composed the song or not. With the enactment of stronger copyright laws later in the century, this practice changed, but Tin Pan Alley sheet music publishers still managed to work together for mutual financial benefit by other means.

Playing the piano became a regular occurrence in middle-class households. If people wanted to hear a new popular song, they would go to the store and purchase the sheet music, then take the sheets back and perform them. Until the phonograph was invented in 1877, this provided the only possible means of transferring and experiencing music.

In the early 20th century, the phonograph and the popularity of radio broadcasting established the record industry. This replaced sheet music publishing as the music industry’s largest force.

Printed sheet music served as one of the first major sources of revenue for songwriters. In fact, for a long while, sheet music was the only source of revenue for songwriters. While royalties from the sales of sheet music have waned for songwriters in the modern music era due to the increased popularity of digital downloads, streaming, records, and CDs, sheet music remains a viable source of income for some copyright holders.

The advent of the Internet in the late 1990s brought a resurgence of printed music thanks to lyric sites and digitally distributed sheet music on websites like SheetMusicPlus.com and MuseScore.com.

What Is a Print Right?

Recall that a copyright carries with it six exclusive rights. All of these apply to print rights. The rights to distribute the copyright and to display the copyright publicly are particularly relevant. Here is the exact terminology for those six rights, along with a common real-world example of exploitation for each as it relates to the print right:

| The Six Exclusive Rights | |

|---|---|

| Right | Example of Print Usage |

| 1. to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords; | e.g. reproduction of a work in the form of sheet music or lyric sheets |

| 2. to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work; | e.g. a conductor transcribing a piece from cello to piano |

| 3. to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending; | e.g. a band teacher scanning copies of a piece for his student choir |

| 4. in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly; | e.g. a poet reciting the lyrics to a popular song at a public reading |

| 5. in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly; | e.g. printing the sheet music to a song and posting it in a public square |

| 6. in the case of sound recordings, to perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of digital audio transmission. | An example would not be applicable because this exclusive right deals with sound recordings, not the underlying composition copyright. |

print music rights

These rights are exploited when music is printed in the fashions described above. However, note that the copyright involved is not the sound recording (master) copyright but the underlying composition (music/lyrics) copyright. Therefore, print royalties are nearly always collected by music publishers on behalf of their songwriters.

What Is a Print License?

A print license is an agreement between a copyright owner (music publisher) and the copyright user. It grants permission to rearrange, display, and/or print the sheet music, notes, and/or lyrics of a song. Even the smallest usage of sheet music, notes, and/or lyrics requires a print license (assuming the usage remains outside the scope of fair use).

A few more examples to provide some clarity about usage:

- If a person wants to print the lyrics to a copyrighted song on the inlet of their homemade CD, they are technically required by law to obtain a print license.

- If a person wants to post sheet music to a copyrighted song on a web page*, they are technically required by law to obtain a print license.

- If Pepsi displays lyrics or music notes on soda cans, they too must obtain a print license.

Print Licenses for the Stage

If a band director wants to rearrange a piece of sheet music to make it simpler for students or to adapt it for the stage, he or she needs to obtain a print license. In fact, theaters both big and small, from Broadway to high school programs, pay a significant amount of money for the right to use the sheet music for a particular play or musical.

For instance, a theater wishing to put on “Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat” must get a license for the rights to the sheet music and lyrics from Andrew Lloyd Webber’s publisher in order to do so. For more information on how to obtain these rights, visit the American Association of Community Theatre.

Securing a Print License

Only three major manufacturers of secular (non-religious) printed music exist in the United States: Hal Leonard, Alfred, and Music Sales. Other specialty sheet music publishers exist for niche genres such as classical or Christian Contemporary Music.

Most of the time, securing a print license is relatively easy. In order to secure a print license, the licensee must reach out to the publisher directly and agree to terms. One must obtain a license for each song he or she intends to print. Many publishers have contact information on their websites. Some publishers even have specific avenues for those who wish to request a print license. In any case, be prepared to relay in detail the scope of usage, the length of time it will be used, the place(s) it will be distributed, etc. All of these factors will help the music publisher determine whether or not they will allow the use, and for how much money.

When making a request, keep in mind that you will only exploit the composition by abiding guidelines and permissions set forth by the rights holder.

It’s advisable to make your written license request to the relevant rights holder several months before the anticipated release date. A standard pint license request should include the following information:

- The party/performance group requesting the print license

- The intended use of the copyrighted material (printed copies, merchandise, flyer, web page, insert, new sheet music arrangement, etc.)

- The name of both the composition and composer

- The volume of copies/uses of the work(s)

When drafting an agreement to license the print works, the rights owner is likely to enforce the following conditions:

- Copies need to be destroyed after use.

- Notice that performance from original or copied sheet music requires additional permission.

- The demand of payment for permission or the purchase of a set minimum quantity of original copies of the music.

Licensees may want to consider hiring an entertainment lawyer before attempting to negotiate with a music publisher. This will ensure both parties establish an equitable contract.

Unlike the royalties from mechanical licenses, the royalties from print licenses are not subject to any legal rate. In fact, they are not subject to any conditions at all. If a music publisher wants to refuse to allow the printing of lyrics to one of their songs, they have the legal right to do so. Likewise, they can charge any amount of money for such usage.

Infringing on Print Copyrights

The importance of obtaining the appropriate license for the use of printed works is in the best interest of composers and creators, but also the licensees.

Infringement and unauthorised reproduction of copyrighted works results in a diminished supply and higher prices for well curated works. For creators and purveyors of printed works alike, this results in constrained revenues.

For users of copyrighted print, the cost of infringement is much higher than the cost of authorization. Legal remedies to a copyright owner for infringing on their work could amount to the following:

- Payment of $500 to $20,000 in statutory damages

- If the court finds willfulness, damages can amount to $100,000

Two years’ imprisonment. - To protect both the licensee and the licensor, a properly authorized print license is a necessary endeavor. As a musical community, we are tasked with upholding proper practices and having no tolerance for copyright infringement.

Click here and download a form to anonymously report illegal photocopying to the Music Publishers Association.

Exceptions Print Licenses

The Retail Print Music Dealers Association outlines the following exceptions for using copyrighted print works without previous authorization:

-

Emergency copying to replace purchased copies, which for any reason are not available for an imminent performance, provided purchased replacement copies shall be substituted in due course.

-

For academic purposes other than performance, multiple copies of excerpts of works may be made, provided that the excerpts do not comprise a part of the whole which would constitute a performable unit such as: a section, movement, or aria but in no case more than 10% of the whole work, The number of copies shall not exceed one copy per pupil.

-

Printed copies which have been purchased may be edited OR simplified provided that the fundamental character of the work is not distorted or the lyrics, if any, altered or lyrics added if none exist.

-

A single copy of recordings of performance by students may be made for evaluation or rehearsal purposes and may be retained by the educational institution or individual teacher.

-

A single copy of a sound recording (such as a tape, disc or cassette) of copyrighted music may be made from sound recordings owned by an educational institution or an individual teacher for the purpose of constructing aural exercises or examinations and may be retained by the educational institution or individual teacher. (This pertains only to the copyright of the music itself and not to any copyright which may exist in the sound recording.)

Royalties for Print Licenses

For single-song physical sheet music (non-digital), the industry standard is a 20% royalty of marked retail price. Given an average price of $5.00 per sheet music, the publisher receives about 99 cents from each purchase. For folios, royalties are usually 10% to 12.5% of the marked retail price. Given an average folio price of $25.00, the publisher receives around $2.80 per sale. For a personality folio, an extra 5% of royalties are granted to the performing artist for use of his or her name and likeness, whether this is the songwriter of the music or not.

For lyrics or music reprinted in books, the rate is approximately one cent per unit, with a $200 minimum attached. For greeting cards, the publisher will usually request 5-8% of wholesale. Reprints on clothing such as t-shirts usually run from 8-11%. Advertising usages, whether in newspapers, magazines, or billboards, normally pay a flat fee that can be $25,000 or more. Lyric reprints in physical albums are usually granted for free.

All of these agreements happen on an individual basis between a potential user of the copyright and the copyright owner. All rates and terms can be negotiated separately.

Term of the Print License

Contracts for print licenses typically specify a term between three and five years. At the end of the license term, the contract usually permits a seller of printed music to sell off unused inventory for an additional six to twelve months. Publishers almost always put in place preventative measures within the contract to ban the dumping of inventory and a practice known as “distress sales” (selling the printed music at far less than normal retail value).

Digital Print Rights

Digital “printing” of music on websites has largely replaced the traditional printing of music on paper. For the most part, interested parties consider sheet music and lyrics on the Internet to be a form of printed music and therefore an exploitation of print rights.

Lyric websites are a significant source of revenue for music publishers. For allowing sites to reprint lyrics, music publishers often receive about 50% of the advertising revenue.

Some companies offer downloadable sheet music for similar prices as physical sheet music. However, there are a few key differences in the types of agreements between these companies and publishers:

Publishers typically request and receive half of the income from these sites, which is a marked jump from the 20% they receive for physically printed music. In addition, print licenses for digital printed music are almost always non-exclusive, unlike traditional print deals. This means a publisher can license the same rights to multiple websites at the same time.

Critical Relationships

- Core: Print rights refer to the exploitation of rights associated with the underlying composition copyright. Music publishers and users of the copyright negotiate and reach agreements for individual print right usages.

- Royalty Collection: Only three major manufacturers of secular (non-religious) printed music exist in the United States: Hal Leonard, Alfred, and Music Sales. Unless a publisher is one of these companies, it will often license print rights to one of these major manufacturers to collect and distribute print royalties on its behalf.

Sources

http://uk.warnerchappell.com/music-licensing

http://www.fabermusic.com/repertoire

https://secure.harryfox.com/public/Licensing-GeneralFAQ.jsp#126

https://www.easysonglicensing.com/pages/help/articles/music-licensing/what-is-a-print-license.aspx

https://musicservices.org/license/terms

http://www.soundreef.com/en/blog/music-licenses/

http://www.dklex.com/licensing-rights-in-music.html

https://entertainment.howstuffworks.com/music-royalties4.htm

Composed by Jacob Wunderlich, Mamie Davis, Luke Evans, Rene Merideth, Jeff Cvetkovski, & Aaron Davis

Want to use this guide for something other than personal reading? Good news: you can, as long as your use isn’t commercial and you give Exploration credit.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.